Knowledge Makers – What to do when Scientists don’t yet “know”?

Scientists are sometimes simply presented to the world as people who “know things”. Whether they be Boffins, Profs, Sci-Guys or Poindexters, scientists are often asked to tell the world what they know. Most of the time, there is very little issue with this, and sometimes simply stating what we know to the public gets the job done. But the idea that scientists always “know things”, is in practice, not always explicitly true.

If we, as scientists, did always “know things”, we would be out of a job very quickly. A scientist’s job is to investigate the things that we don’t know – essentially taking Donald Rumsfeld’s known-unknowns and making them known-knowns – all in the name of advancing our collective understanding as a species.

As always, the German language is able to encapsulate this idea perfectly in a single word. The everyday translation of Scientist into German is Wissenschaftler; a word that is built from two other words, Wissen and Schaffen, meaning Knowledge and Create/Make, respectively. Therefore, a Wissenschaftler is quite literally a “Knowledge Maker” in the German language. With this in mind, scientists could therefore be viewed not as people who necessarily always know things, but instead as people who forge new knowledge in the peer-reviewed smithy of Castle Academia. Whilst this difference may be subtle, I feel that it would be beneficial to make this difference a larger part of our collective persona as we work and communicate with the general public, especially seeing that scientific communication has failed in places when it was needed most in the last few years.

Skepticism in Science

Recently, I had an acquaintance tell me that they were skeptical of the corona vaccine, despite having had previous vaccines for other diseases with little-to-no concern. When asked why they were hesitant this time around, they replied “Well, because the scientists can’t make up their mind about the corona vaccines. One day they say the vaccine is safe for everyone, then a few weeks later it’s only safe for people over 60 years of age… and then different versions of the vaccine have different side effects… So if they don’t know what it is doing now, how can they possibly know what long term effects there could be further down the line?”

To some degree, despite personally trusting the science, I can sympathise with these questions and understand where the concerns come from. The apparent changes in opinions and advice – sometimes on very short notice (in no way helped by the politics that come with it) or with surface-level contradictions – do not make it feel like the information is coming from people who (somewhat classically) “knows things”. This in turn may cause people to question if the advice givers can be trusted, and so seek out alternative advice in the hope to obtain a more “definitive”/”stable” answer, even if those answers may objectively be less reliable.

So how do we deal with this issue? What fundamental things do we need to change to keep the trust of those who may not have the scientific experience, or simply patience, to keep up with the changing advice and discoveries, as we scientists try to figure things out – whether it be in crisis or more “normal” times?

Gathering Knowledge

Some of the problem I feel lies with how the majority of us obtain knowledge from an early age. As children we constantly turn to those who are older than us for information. Whether it be our parents, guardians or teachers, we go to those with experience that vastly exceed our own to seek out the answers to the questions we have. Generally at that age, we accept what is told to us without much quarrel on the assumption that the ones telling us simply “know”, and for the most part this suffices. Primary (and to a degree secondary) education is “well-established”, and at this stage we are rarely ever brought into contact with new and contemporary discoveries outside of the “And Finally…” segments of the 6 o’clock news.

But when one gets used to being fed information shaped by the giants who came before us, whose shoulders we now stand upon, it causes difficulties on those few occasions when people run into something that is truly unknown. Even if a person comes across something brand new to mankind, I suspect a lot of the time the first thought is along the lines of : “With 7+ billion people on this planet, surely someone must know something about this?”

I know that my past self was guilty of thinking this way.

First Encounters of the Unknown Kind

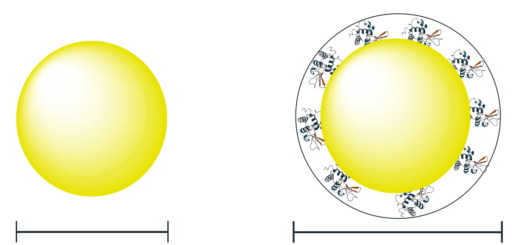

In one meeting towards the end of my final-year undergrad project, I was sat across from my supervisor, countless graphs splayed out on the table between us. Hours had been spent trying to understand the results that lay before us. We had a hypothesis of what could have been the scientific interpretation, but after weeks of literature research, we couldn’t find anything solid to back it up. When out of frustration I asked her why we couldn’t find additional evidence to help our understanding, she replied “Because this is likely where our collective knowledge stops. What we are looking at is something that has not been seen before and is somewhat still unknown. It is therefore now our job to interpret the information that we have, as best as we can, with the hope that we can guide people in the right direction until we have more information.”

Whilst the result was nothing earth-shattering, I still feel lucky to have had an example of the limits of our collective knowledge so clearly placed in front of me in a relatively calm manner. I know that this experience is one of the reasons why I still pursue science – to figure out that one thing that no one else has done so, and push our collective knowledge that little bit further. I suspect that most people who pursue science have experienced similar moments as well.

Unfortunately, not everyone has had that moment.

Knowledge is not something that is set in stone. It is fluid and ever changing. It is dependent on new and better understandings. A discovery made tomorrow could irreversibly change the way that we understand a subject. Previously, I touched upon Donald Rumsfeld’s different levels of “knowns”, i.e.:

- The known–knowns – those things we know we know.

- The known-unknowns – those things we know we don’t know.

- And the unknown-unknowns – those things we don’t know we don’t know.

Whilst the journey of unknown-unknowns and known-unknowns becoming known-knowns is a story that scientists know all too well, it is not one that I believe that is on the radar, let alone front and center, in the minds of the many that are not directly involved in the active scientific community.

Science in Action

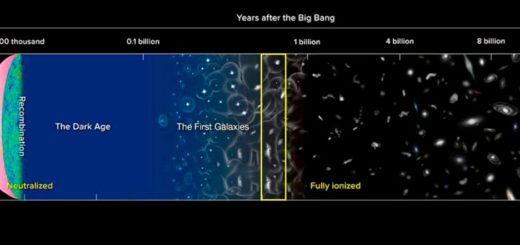

The events of the last couple of years of the pandemic have been fast paced. At the end of 2019, we had the initial discovery of the virus – i.e. an unknown-unknown becoming a known-unknown. Since then, in a very short space of time, we have gone on to studying what the effects of the virus are, determining how best to protect ourselves from it, and even going as far as the development, testing and distribution of vaccines to fight back against it. It is only now that our collective understanding of the virus and the vaccines used to fight it are transitioning from being a known-unknown to becoming tentative known-knowns.

In many respects this is a triumph of science. It shows what we can do when we work together on a single goal – and that is phenomenal. It is truly an achievement that scientists can take pride in. However, for many non-scientists, it is quite possibly the first time that they have seen science in action – the so-called “Knowledge-Makers” actively working in real time on new discoveries that will directly affect their daily lives. Most advice and scientific knowledge before now, appeared in a somewhat static format; i.e. You went to the doctor for an ailment, they told you some advice and you accepted it, assuming that the solution has long been tried and tested. Yet now, countless people are seeing for the first time knowledge being created and revised in real time, as we interpret the information that we have, as best as we can, with the hope that we can guide people in the right direction until we have more information.

Paths forward

Being referred to as someone who always “knows” is always a nice ego boost. It makes us feel important. But that warm, fuzzy feeling of importance does not help when people no longer feel that they can trust us in times of need. If the events of the last couple of years have confirmed one thing in my mind, it is this: When it comes to scientific communication, it is clear that simply telling people what we know is not enough. We need to improve how we teach people about the scientific method itself and the processes that we go through to shape the new knowledge that we obtain. We need to find better ways to make clear the boundaries of our knowledge at any one time, yet simultaneously, build people’s confidence to trust us as we discover more and push those boundaries out. We need to have people understand that scientists are not simply people who “know things”, but are also people who are able to craft new knowledge. And with all craftwork, that process takes time and fine-tuning.